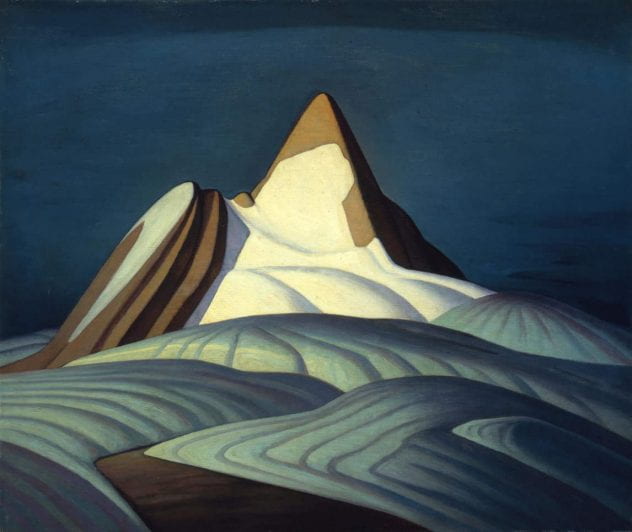

A mountain stands alone with snow slipping off its peak in a field swimming with white hills. The peak is all a person and an idea, a motive, a thought. By casting dramatically detached imagery from the centerpiece and the environment, Lawren Harris’s Isolation Peak, Rocky Mountains, and Northrop Frye’s biography in The Canadians: Biographies of a Nation relate the purpose of isolation in Canadiana’s extensive framework.

In like manner to the solitary peak in Harris’s painting, every person is the isolated peak in their own life. No one has, is, or ever will journey through life with a permanent, human other. Take the love of Northrop Frye’s life, Helen Kemp. Although they were married over fifty years before she passed away, she was not with him at his birth or death. Even his profound visionary, dream-like experiences he could not share with her. Of course, recording such experiences as stories and biographies can retell the experienced events, but such retellings do not come close to the real experience.

at the heart of [Frye’s] work is a series of sudden flashes of what seemed to Frye to be profound and intricate insights that would require a vast amount of rigorous thinking to explore and to make comprehensible both to himself and to others…

one day on his way home from school was struck by a sort of spiritual and intellectual searchlight beam. He said that he had known at the time it would take him years to find out what the sudden clarity meant, but he also knew right then and there that it would change his life. (Watson 191-192)

And the work that revolves around Frye’s flashes has drawn the universal attention and rigor to understand his interpretation of literary criticism and numerous other subjects such as myths and metaphors and religion of every respectable English scholar and many English students.

Despite a journal entry that he wrote on his sixtieth birthday reading, “I have arranged my life so that nothing has ever happened to me, and no biographer could possibly have taken the smallest interest in me” (190), he became one of the most influential literary critics and theorists of his time. Often, without knowing in their lifetime, people assume that their stories and lives are as average as humanly possible, simply because they feel they are being themselves, and since everyone else is themselves, every human life on earth contributes to the heap of similarity.

Although Frye’s work happens to be influential and his legacy remains unmatched, his life story serves as a guide to understanding the theme of isolation in Canadian literature and art. When writers and artists set about with their work, very few achieve exactly what they had in mind, since even what they had in mind was likely an incomplete thought or a vague aim. But as the story feeds off the inspirations and ideas of the creator, it grows and matures to become its own, unique being, existing as a sole entity in the universe.

From Isolation Peak to biographies and novels, every Canadian work is the product of a distinct mind, one that is isolated not because others are not, but because in their psyche no one can completely join them. Even copied ideas are formed from idiosyncratic motives and feelings, unparalleled for eternity because of the singular circumstances and situations of the artist.